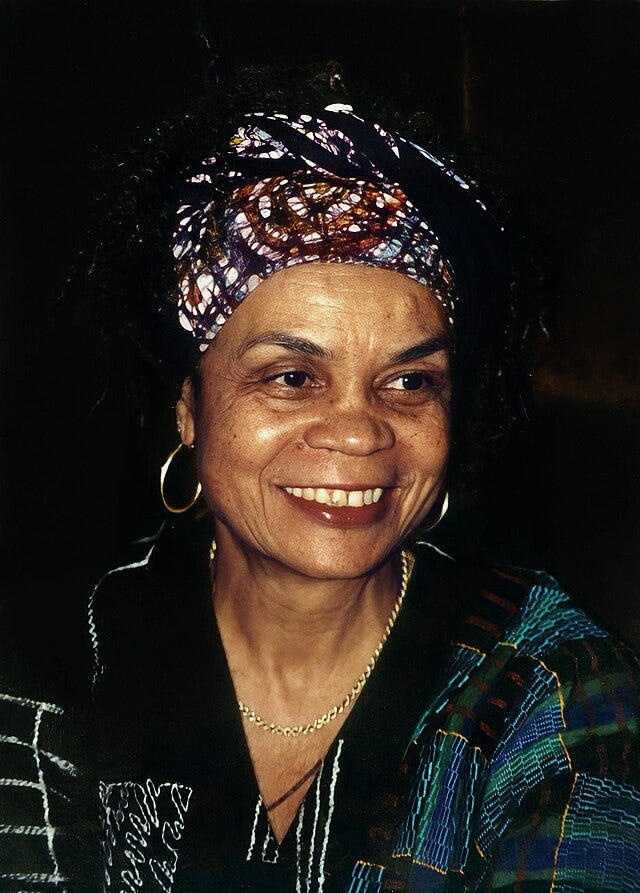

Teaching Hidden Histories - Lessons from the Brilliant Sonia Sanchez

The poet was among the first professors to teach at the first Black Studies Department established at San Franciso State College

Who is qualified to teach Black history, literature, and culture?

When looking back at the history of the Black Studies movement of the 1960s, there are two points of significance that should inform how we deal with the current propaganda in education.

For one, Black students led a multiracial coalition that demanded the incorporation of Black Studies in higher education. Still, they did not wait for the powers that be to drag their feet, shuck and jive, and derail the process. Students at San Francisco State College (now University) established their own Ethnic Studies Experimental College in 1969 without the cooperation or permission of college administrators. Like the Freedom Schools of 1964, the Ethnic Studies College was an independent and “parallel institution.”

Secondly, students had enough sense to realize that the people most qualified to teach Black history, literature, and culture at the liberated Ethnic Studies College were not the usual suspects - professors with doctorate degrees, peer-reviewed scholarship, and many years of academic training. Student activists identified that the real experts of the human condition were the revolutionary artists.

The students hired Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, and Askia Touré as the first professors of the Ethnic Studies College. As pioneers of the Black Arts Movement, they brought innovation, dedication, and courage that made them the most qualified to make higher education relevant to the people and of service to community needs. It was the artists - the poets - who are the healers, according to Sanchez, who forged new paths for the emergence of Black Studies and Ethnic Studies, which ultimately transformed higher education.

This was not an easy task. Teaching Black Studies was serious and dangerous work.

In 2004, Dr. Joyce A. Joyce published Black Studies as Human Studies: Critical Essays and Interviews, which documents the experiences of the artists who were called to join the Experimental College at San Francisco State. Below is an excerpt of Sonia Sanchez’s interview detailing what was at stake as they embraced the mission to teach this truth - the Black experience is a powerful exploration of what it means to be human.

EXCERPT

“Black Studies, as we originally thought of it at San Francisco State, was to interrupt and invade the study in the universities of America of White Studies, of what was going on in the various curricular concerning history, English, social studies, sociology, etc. We intended to bring into those spaces the study of African-Americans, of Black folk, and the impact they had in the country and the world. Okay.

So we, as writers, professors, educators, began to insert African-American people of color on the world stage, and we said, look, we have contributed in such a fashion that you cannot teach history in a vacuum of European and White aesthetics. You’ve got to deal with the history and herstory of Africans in the diaspora.

It was, at the time, an amazing concept. Not amazing because it had never been thought of, okay. It was amazing because the university had closed up the study of people of color, okay, as viable intellectual beings worthy of study, worthy of discussion, worthy of any kind of place in the university intellectual setting. All right.

So we begin - I began to teach creative writing with all Black writers. Some Latino writers also. We include the Asian writers along the way if they meet some of the criteria that I set.

And I began to teach Afro-American lit. The first day I walked into a classroom, I put on the board people from Frederick Douglass to Du Bois to Langston Hughes to Richard Wright, Malcolm, and MLK. The only names they recognized were Malcolm and MLK. They did not recognize Delaney or Garvey, Du Bois, or any of these other people.

So I’m saying in 1967, in a place called San Francisco State College, we began to bring into the curriculum the idea of the genius and the importance of not only the African-American experience, but the African experience in the diaspora. It was a revolutionary idea, my sister.

Now it’s not so much. Maybe it still is. But at that time, it was a revolutionary idea to insert into the English Department the study of African-American literature.

...

The reason why these big companies decided to republish people is because there were Black Studies. There was a call and a need for this. I still remember in San Francisco the day that Cane came out. We went to the library. I took my students to the library, and I can say to you in a terrible fashion that I took that Cane book; you know, I was so angry because it took all of this, this kind of history, this kind of calling of the book companies. We called the book companies, and they reprinted it.

They understood there was this uproar in Black Studies, and this uproar with people wanting to read Black things, so when Cane came out, I took them to see it in the library. That was a historic moment. They saw Cane, Jean Toomer’s Cane, in the library.

And I cried, you know, because you see, the whole point of teaching Black Studies is not for self-aggrandizement. The whole point of teaching Black Studies, my sister, is to bring history that was buried, to bring up Du Bois, who was buried. Because I taught Du Bois at San Francisco State, the FBI came to my house and knocked on my door. I open the door, and this FBI agent stuck his head in my face. You’re out there teaching. He had my landlord. He told him to put me out.

…

What all that was about was that this government had successfully kept Du Bois from being taught, Robeson from being taught, and Garvey from being taught. And what we did, you must hear this. What we did with Black Studies, why it was so critical and why this country had a terrible campaign against Black Studies is that we resurrected people who have been hidden and by doing that, of course, I got on the list and all of us got on this list from the government, and that was how we dared resurrect people who have been hidden by this country, and so we brought back Souls of Black Folk. It’s amazing. A man who said black folks have souls at the turn of the 20th century.

We brought back Garvey and the whole idea of Africa for Africans. We brought back Paul Robeson, the man who said this is not art for art’s sake. You know what I’m saying? You have got to figure out what you’re saying with art, and he certainly used his art well in changing the country and the world.

So I mean to have chosen those people, along with Langston Hughes, along with all these other people, from Delaney and all the way back. People came into the classroom, and you’ve got to understand, they sat on the floor. When there were no seats, they sat on the floor. They sat outside the door. There was a crowd outside the door because they hadn’t heard this.

And all those names I have written on the blackboard that we discussed during the semester, and those people came in grateful to learn this, and they were angry because they had neverheard of it. You know that’s what I’m talking about.”

THEE Baddddd Sonia Sanchez taught one of the earliest college courses on African American literature as well as one of the first courses on Black women. As a cultural producer, Sanchez helped to shape the Black Arts Movement. Yet, her role in shaping the Black Studies Movement is a powerful lesson and affirmation that deserves greater recognition.

So, who are we to be discouraged when we have a legacy of revolutionaries teaching the truth under fire? Black Studies is still in the making…

Thank you, TaSha!